Lesson Learned in the Wild West of Immersive Arts

No longer the domain of goggles, domes, or museums, the words “immersive experience” have found their way to cities. This past November 3rd, Aurora, a Light-Video-Sound Biennial art event in Dallas, Texas, hosted artists from around the world to transform the downtown civic area with new media installations.

Fabian Knecht’s Freisetzung had smoke billowing over the Soviet-style inverted pyramid City Hall. Miguel Chevalier’s Digital Icons, emoji-like projections converted the concrete plaza into an interactive tapestry, and in Alicia Eggert’s sculpture billboard, “All the light you see is from the past” flashed and then faded—just a small sampling of some of the 28 artworks presented.

But what does new media have to do with virtual reality? Practically kissing cousins, both merge cutting-edge technology with art (or art with cutting-edge technology depending on your perspective) and so share the same vocabulary and desire to engage viewers across multiple dimensions.

Stop Staring

On this particular dark and stormy Dallas night, for example, visitors had to navigate the barely-lit city pathways to encounter the works; some were nestled among trees or in the recesses of the convention center building, Compare these interactions with the static gaze required of 2D paintings displayed in traditional museums. New media is more like VR than watercolor.

At Aurora, the physicality of the terrain, the cloud-heavy evening sky, the texture of the façades became part of the work. “Immersive experience”–VR’s favorite descriptor–was mentioned repeatedly by the curating teams as part of the artists’ objective.

In fact the language of the curators, Dooeun Choi (NYC), Nadim Samman (Berlin), and Danielle Avram (Dallas), as well as Monica Salazar, the Berlin-based Director of Programming, constantly referred to concepts like “other worlds,” “the sense of immersion,” “the digital vs. physical worlds”—phrases which could be straight out of a VR gathering.

Culture Matters

Besides the obvious creative inspiration, VR-makers have a lot to gain from such events. Seeing large-scale works with artistic merit helps break down the barriers for investing in expensive pieces, one of Cinematic VR’s biggest challenges. Thanks to the long-standing practice of artistic patronage, culture is an easier investment to make and budget for not only for cities and government, but also for private benefactors and foundations.

Increasingly well-known, established artists are leaving their preferred mediums behind to try VR. Performance artist/musician Laurie Anderson debuted The Chalkroom, Marina Abramović filmed Rising (both in 2017), and Anish Kapoor created The Body—Fall (2018). The high profile artists attract more attention from the philanthropic set and prime them to support VR work, too.

Currently it is location-based VR that has been the bread and butter for many Cinematic VR production companies and not grants or subsidies. Cities might be the next go-to funding source as cities need projects that connect deeply with its citizens while at the same time generating economic impact. There is no reason why virtual reality could not duplicate immersive art’s public appeal.

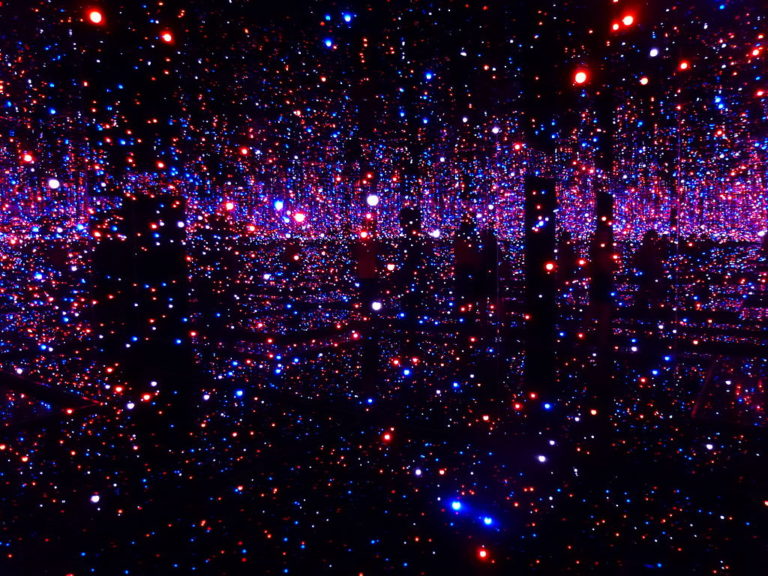

Take Yayoi Kusama’s work, for instance. Kusama’s ability to create an expansive cosmos of shapes, light and texture that invites viewers to enter her universe, is iconic. Her Infinite Obsession touring exhibition in 2014 had more than two million visitors in Central and South America alone. Her latest retrospective, Infinity Mirrors–an exhibition centered around, what else, mirrors–has been nothing short of a global blockbuster sometimes with three hour waits in line. The resulting tourism revenue and positive press has bonafide economic advantages which should encourage cities to further subsidize powerful, experiential work.

Watch and Learn

Another reason, city-sponsored immersive arts are worth VR-makers’ attention are the way artists experiment and deep-dive into technique and technology. Herman Kolgen, who performed Isotopp in the middle of a roadway tunnel at Aurora, is known for making the invisible visible. Isotopp was described in Aurora’s press release as:

Even if the premise is overly highbrow, the resulting sound Kolgen produced was interesting in the way it was loud and rumbled and then was followed by a quiet plink. Kolgen’s sound completely penetrated the space–exactly what VR-makers must do in order to ensure a captivating moment. The same could be said for Miguel’s Chevalier’s playful Digital Icons. The projections would dart and dance according to where the viewer stepped. Are there useful technical considerations as to where he places sensors? Artists might have answers.

Designed for the Feels—and the Pics

Immersive art does not always have to be a sophisticated experience. The Museum of Ice Cream, an Instagram utopia offers perfectly pastel ice cream-themed rooms for snaps and selfies. It has had $20 million in ticket sales since it opened in 2016, ballooning to four locations. The relationship with cities has since strained due to hygiene and plastic ice cream sprinkles. Sprinkles would accidentally stick to patrons when exiting the museum and end up in storm drains causing environmental pollution. The Museum of Ice Cream racked up a significant number of citations and violations meaning you can’t take a municipal relationship for granted, either.

Meow Wolf, “an arts and entertainment production company that creates immersive, multimedia art experiences,” contends it provides the city of Santa Fe job growth. Meow Wolf negotiated with Game of Thrones author George R. R. Martin for a 10-year lease of his Santa Fe property to build a permanent immersive installation that “transports audiences of all ages into fantastical, explorable realms with discoverable narratives.”

In other words, they are colorful, tactile places that mimic a stereoscopic environment, but one that already brought in $800,000 its first year of business.

Hi Mayor. Let’s Talk Business.

The ebb and flow of art to VR and VR to art is not surprising given that they share a common desire to create a transformative experience. If like Aurora, and a city partnership can be established, it can become a springboard for greater exposure for the immersive arts in general and VR in particular.

The 2015 edition of the Aurora Biennale attracted 50,000 visitors in seven hours—a level of engagement usually noticed by city fathers. As cities dabble more in new media arts, the time to collaborate with cities on VR projects nears, whether it is to promote culture, tourism or job growth.

As Aurora proved through their skillful curation around new media, the future is still proving to be all about the “immersive experience.” (The way it has always been for VR).