Syd Field Can’t Help You Anymore

Eyes blurry, aspirin next to the glass. Screenwriters have it tough. After all, only 10% of Writer’s Guild submissions are ever made. The foundation of cinema and television–the screenplay–requires craft.

Writers have to take into account structure and proper formatting, use short pithy dialogue, and build the story arc into a satisfying conclusion—all while developing compelling characters and telling a fascinating narrative.

Much of it holds true for writing for VR, but since there is a new option for the audience to join the story from an immersed perspective, and no longer be swept along as a passive viewer, the added complexity is no shocker. Virtual reality is a new, groundbreaking art form, but there are no Syd Field screenwriting books to guide you.

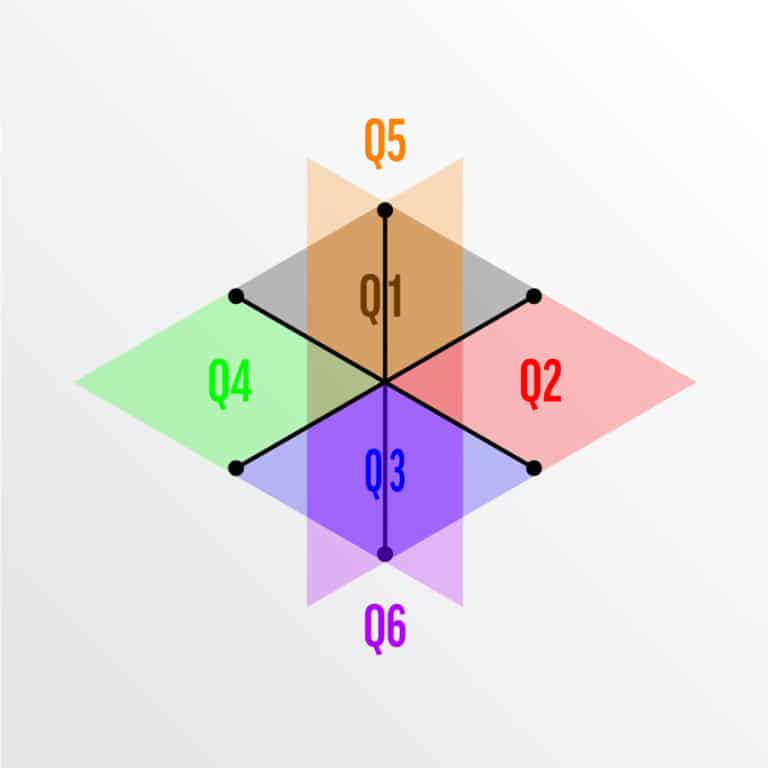

What we do know is a in VR has to take ordinary script elements, like timing, transitions, and sound, and give them greater consideration. And what used to be an afterthought for many traditional Hollywood players (not all, and certainly not the likes of most arthouse directors), the background space now has full dimension, but for VR, an array of possibilities. If traditional storytelling is linear, in VR there are six quadrants: right, left, up, down and above and below.

The VR screenwriter has to write while thinking about sightlines and background noise, plus use environmental cues to direct the viewer. At the same time, the story has to be able to branch into sub-stories, adding layers and options.

Let’s look at the breakdown:

Opening

Back since the days of the cavemen, stories were told and the rapt audience had to listen, imaging what took place. Perhaps some cave drawings punched up the process visually, but epochs later in VR storytelling, the first decision a writer needs to make is asking if the viewer is a character or an observer. The listener is in the story, which is also termed presence.

The thrill of VR stories is they aren’t just seen, as traditional cinema and television offers (“the flatties” as they can be cheekily referred to), but stories are lived and felt. Writing has to take that mindset to properly make the script come alive.

Perspective & Tension

Where does the character enter? In traditional film, the director chooses the POV. but while true for VR, as well, the audience has agency to explore new angles. Establishing the eye level helps anchor the viewer. The different fields, or quadrants as they are sometimes termed, indicate the broad possibilities where the story might head. Just as you walk outside your front door each morning and have the option to turn right to get a double espresso or go left if you need to run towards the bus stop, the viewer has choices just like real life. Your character even may not look down to see the jungle grass or city asphalt, but the fact that it is there enriches the experience.

The additional fields expand the storytelling possibilities because they add chance, which in turn creates tension. Will a pigeon swoop down from above? Will there be chalk drawings on the sidewalk? The expanding spatial canvas gives the viewer options right and left, up or down, but also above and below. The broad range of spatial options help create tension—storytelling’s oxygen.

Some VR writers (and some do not!) swear by using color to distinguish between the quadrants:

POV

In regular writing perspective is limited to first (“I), second (“you”), or third (“he” or “she”). In film, the camera point of view is done from third perspective; the audience witnesses the main character. This can be done with or without an off-camera narration (limited–knows one side of the story, like Harry Potter in the Chamber of Secrets, or omniscient, like Alec Baldwin’s narrator in The Royal Tenenbaums–he knew everyone’s perspective). But with VR, all of a sudden there is a first person perspective and (usually, but not necessarily) a third person perspective. Do they coexist? Is one more powerful than the other? Point-of-view takes some attention and a whole new strategy of thought.

Sound

Whereas in traditional writing sound often looks like: “she walks up creaky stairs and her cell phone RINGS.” Most of sound is a fixer-upper done in post, but in VR it is essential to consider holistically in the writing phase. Just as many sounds happen at once in real life, these have to be taken in consideration from a 360° perspective, too.

Even if a scene is shot in an apartment building, where someone is walking up creaky stairs, outside sounds like sirens wailing, or the blare of the neighbors television, conversations might even overlap depending where you stand.

Opening the door to an apartment would lead to sounds coming from an aquarium or the hum of an old refrigerator based on which direction you head making sound layered and multidimensional. Sound has to expand or contract according to spatial movement, but it is also what keeps the viewer immersed (which is why it has more prominence in VR).

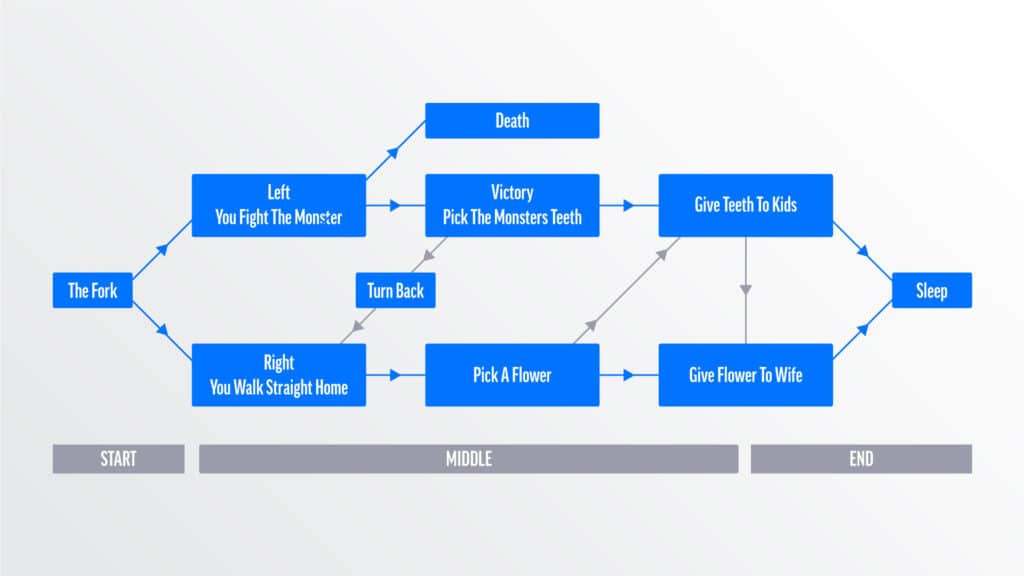

Story branching

In VR, storytelling is like Sliding Doors on steroids, only sans Gwyneth Paltrow. Linear storyline goes from A to Z, but now subplots can erupt at points D, J, P or Q or anywhere else. These elements add to the experience because they simulate life and substantiate the viewer’s immersion.

It is important to note, that while a viewer’s agency approximates the choices he or she can have in real life, it must still be contained within a narrative of some kind. VR storytelling requires more skill, because the writer has to thoughtfully weave choices together into the overarching storyline.

Sensation

Aaron Suduiko writes that VR “can turn the passive experiences we observe in a film into felt experiences.” It means not only telling a story through dialogue, but through sensory imaginings.

Environmental cues can direct the viewer where to put their attention and artful transitions will be critical to the seamless sense of the experience so there are fewer set-ups and cuts.

It has only just begun

Obviously this is only a smattering of the concepts and decisions a writer has to make in virtual reality. For every person you meet in VR right now that says, “these are the rules,” you will meet one more that swears by the pirate mentality of “there are no rules.”

The most important questions to ask are “Is this a story that will keep my audience interested,” and “Does this decision make sense.” As long as your story can convey that essence on paper in a way that is efficient for the actors and production team (not to mention financiers), you are headed in the right direction. Scriptwriting will continue to evolve, but just as writing still relies on grammar, VR screenwriting still relies on a compelling story.