Gayatri Parameswaran: “Tips on Filming VR in War Zones”

Bombay-born but Berlin-based, Gayatri Parameswaran, another selectee of the Kaleidoscope Development Showcase shared some of the harrowing behind the scenes from her documentary piece Home After War and her Kaleidoscope piece Kusunda, which immerses the viewer in the world of a dying language.

listen on your favorite platform

Justine: Justine Harcourt de Tourville, still at Cannes XR and it’s really fantastic because I am able to speak with so many makers and shakers and doers and creators of virtual reality. And today that is still the case because I’m going to be talking with Gayatri but I have to ask you to introduce yourself because you know, I can’t say your name correctly. Please. Would you give us the honor of introducing yourself?

Gayatri: Thanks a lot Justine for having me here and for speaking to me. My name is Gayatri Parameswaran and I am an immersive creator and journalists from India and currently based in Berlin where I go run Nowhere Media, which is a storytelling studio that’s really working on harnessing the power of immersive technologies for social impact.

Justine: I remember seeing you in Berlin where you’re based at VR Now and you had done a really great piece. It was about war, the effect of war. You want to talk a little bit about it?

Gayatri: Yes. Home After War is a room scale virtual reality experience that was created as part of the Oculus Vr for good creator’s lab in partnership with the Geneva International Centre for humanitarian demining. The Home After War is the story of an Iraqi father who lost two kids, two sons, two of his sons to an improvised explosive device in the neighborhood. What’s happening in Iraq now after the fighting with Isis has ended is that refugees and internally displaced people want to come back home, but then homes are not safe because they are contaminated by improvised explosive devices or booby traps. So for me it was really incredible to have this notion that a home is unsafe because for me, home is where I feel the safest and the most secure. And for people like Suadad who is our protagonist in the piece, it’s not, it’s a very ambiguous relationship with your home. So when you come back after two years in a refugee camp, of course we are delighted to be back home. But also you’re not sure if it’s going to be a safe place. there have been instances where people have come back home, tried to open a open a door and that has set off an explosion, our turn on the electricity and that could set off an explosion. So this is really an unprecedented challenge. that’s facing the, the civilians who are returning back home in Iraq and our piece home after war, which recently won the best use of immersive arts at South by southwest is really trying to highlight this issue.

Justine: Well, I remember seeing snippets of it, I remember seeing the impact and indeed it’s a great medium to tell these kinds of stories and to, to bring it home for people. So very good job and congratulations with the prize.

Gayatri: Thank you. Thank you so much.

Justine: Let’s talk though, we’re now here at Cannes. I’m also a very nice sunny place, so a great respite from Berlin. what have you been doing here?

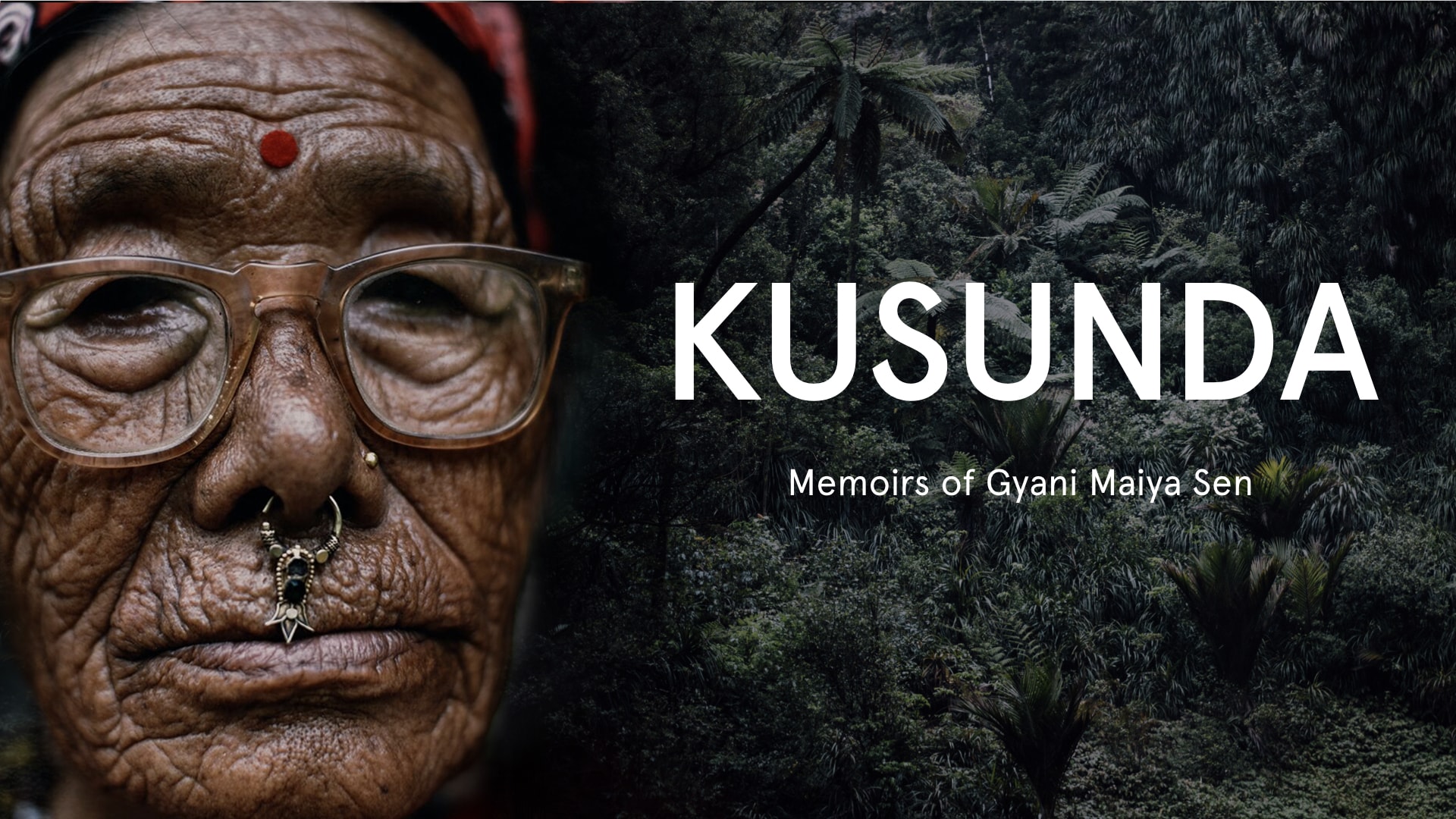

Gayatri: So apart from showing home after wore at the virtual arcade here, I’m pitching our upcoming project Kusunda speak the unspoken. Kusunda is is a documentary, a virtual reality experience in which you meet Ganny Madison who is an 83 year old indigenous woman

Justine: and from where?

Gayatri: From western Nepal. And she’s the last speaker of her language and the guardian of a culture of our culture. So she’s also a bad ass inspiring figure and she realizes that she, you know, the language could die with her and she wants to do everything she can to pass it on to the upcoming generations. So the virtual reality experience Kusunda is part of our… it basically compliments her efforts. And in this expedience you use your voice to speak in her mother tongue and triggered interactive journeys into her past and her thoughts. And we really use, want to use voice because oral traditions are very much at the heart of ancient languages like Kusunda that do not have a script. And by involving the user in speaking the language, we also make it empowering to be part of this experience for the user who will then play their own part to not let the language fall silent.

Justine: And you’ve been doing this as part of the Kaleidoscope showcase.

Gayatri: Exactly. So last year in November, running from Kaleidoscope VR invited us to be part of the Dev lab that they organized together with riot and Oculus. And those three days were amazing in terms of being very inspiring, forcing you to think out of the box and get inspired from other disciplines to create amazing virtual and augmented reality experiences. And since then we’ve received seed funding from kaleidoscope VR.

Justine: Fantastic.

Gayatri: And we are now, I’m looking for further funding and we’ve made some applications. We have coal production partners on board and yeah, that’s where we stand. So we are here at Cannes to pitch the project and find further coproduction partners and collaborators perhaps as well as funding opportunities.

Justine: And how has the festival been for you?

Gayatri: So I arrived yesterday, and this is my first time at Cannes. I’m a real newbie. but it seems like an amazing place. It’s crazy, right? Cannes is huge. Like what’s going on is huge and it’s hard to find your grounding, but I think the Cannes XR section is pretty they’ve done a great job at concentrating on, you know, the focus is really here and you walk down one aisle and you meet a lot of players in the field and that’s, that feels like a community.

Justine: I felt the same and there hasn’t been someone either new that I’ve never met, but we’re talking to and only interesting stories so far. So you’re in good company.

Gayatri: Yes. It’s really fascinating also to see the other projects that are here as part of the showcase as well as just meeting people who are, you know, moving and shaking as you call it. And then, you know, and just being part of this crowd who is very dedicated to take this medium forward.

Justine: This is exciting. And one thing I want to shout out to is, unlike with a lot of festivals where you’re certainly timed and slotted and you have a harder time, I’ve had easier access. I don’t know if this has been the same for you and being able to see some of this cutting edge work or the quality work that we all wait line a long time to see. So have you, have you seen anything that’s really,

Gayatri: I haven’t yet, but I’ve booked, so here it looks like it’s okay. I’ve booked for tomorrow. so that I can go and check out some of their stuff. And I think the library is a good way to experiment. Getting, giving people a choice of, you know, some of the best works from the year and showing it that and letting them pick which ones they want to, they want to see.

Justine: Yeah. I’m a fan of the system. So, you know, just being able to see more work as people that support the industry, you know, it gives us a sense of who’s doing what, who can we collaborate with more. helps us make better connections, which I think is part of it.

Gayatri: Exactly.

Justine: Anything you want to share that you’ve learned along the way of making VR and being in documentaries, storyteller? I mean you use real life subjects with real life problems, anything that you’ve learned that you want to pass on to others.

Gayatri: I think as a documentary maker and a journalist, it’s fascinating for me, the places that I can take my audiences doom as part of the journey. and it really is, it functions when you have virtual reality, when you wear the headset, it functions much, much faster or easier than, I don’t know. You can read a very immersive text and you can listen to a really immersive radio show. And I think all of that can work somehow with virtual reality. There is a sense of presence which is unmatched in any other medium.

Justine: True.

Gayatri: And something that is, you do not have to imagine it. It’s there. And I find that fascinating to exploit as a documentary maker and as a journalist and to take people sometimes to confrontative situations that they might not otherwise be put in. And sometimes to place them in someone else’s shoes that they might not otherwise have the opportunity to do. So I think that’s what I am really, really excited about and I’m really excited about seeing how learning, how people are behaving in these situations and these scenarios. For me, it’s almost learning more about human psychology and about how people react to certain scenarios and, and it’s replicable so I can do the same experiment showing something to many different people is possible in Vr than in real life experiments. So I think that’s what’s very, very fascinating for me working in this medium and to really use it to create social impact. And our last piece ‘Home After War’ is currently being shown at the United Nations in New York. it’s an exhibit at the visitor center and it’s running until the 20th of May.

Justine: Well, congratulations.

Gayatri: Thank you.

Justine: That’s another accomplishment.

Gayatri: Yeah, thanks. And I think that’s, I met some ambassadors who, diplomats who were watching the bees and they came out of the experience and they said, you know, I really know the issue very, very well. I know the facts, the figures, the strategies that we need to create to solve this problem. And even when I’m on the field in Iraq, sometimes I cannot take 20 minutes to spend time with one family and one person and listen to their story. And it’s very important. What do you do here? Because it gives it makes sense. This is why I started doing what I do. And you know, along the lines, sometimes even experts forget why they do what they do are, are disconnected.

Justine: That’s true. I mean, we get into a very bureaucratic, in some ways we have to shut down from the 4:00 AM to protect ourselves from this very unpleasant reality. so it’s good to be reminded again and short of going to the field or going to these located in remote locations and being in this situation, it’s good to have access again. So I do run to ask, I mean these are dangerous places that you’ve been and you know, what were some of the complications of filming in such a potentially, you know, booby trapped home. I’m sure it was cleared, but I mean there’s some real real life fears happening.

Gayatri: Yeah, that is some real risk to it. We would always traveling with Amin convoys. So that level of security was amazing to have. we also had private security with us, so we felt very safe. But of course you don’t know how safe you really are because sometimes we were doing some research and the army, you know, the captains told us, just stay on the track where you see that we’ve vehicles have moved. Don’t step one, don’t take one step to the right or one step to the left. You know, just stay because that’s the path that has been kind of tried and tested. So nothing will blow up if you stay on the tracks of the weakness. The entire line. Exactly. Good.

Justine: Okay. Well that’s good tips. Yeah. Yeah.

Gayatri: So but apart from them that there’s like so many production related hassles as well.

Justine: Right. So because of having electricity maybe might be an issue.

Gayatri: Yeah, that’s something we didn’t phase as much, but because we were seeing in, in Baghdad and we were doing our research and shooting and filming in Fallujah, the distance between back then and Fallujah is about 75 kilometers. But that says nothing about how long it takes to reach Fallujah from Baghdad.

Justine: Wow.

Gayatri: Because there is a really complicated checkpoint cross between Baghdad and Fallujah and that’s like the, it’s, it’s controlled by five different bodies. So the military, the intelligence, the interior ministry, the army and the police,

Justine: Goodness gracious.

Gayatri: And you have to get a clearance from all of them to be able to cross in and out. And there’s always something that’s missing. I mean, fair enough because it’s a country that’s facing a lot of problems when it comes to internal security. So I completely understand that. They want to be absolutely sure who’s passing through and coming back in . And then you have equipment that looks, you know, VR equipment is not very commonly. It’s hard to explain what it is. So we spend like hours and hours at checkpoints and that means that the time you have to actually go and do your work is very limited because there’s also, you know, by sunset you need to be back in the hotel because it’s not as safe to be on the road when it’s late. So you had maybe a day that would be four or five hours and you had to be very, very concentrated and get as much work done. And we were working, we were using photogrammetry to create, the piece. And, sometimes we had to, you know, when the light went down, we had to… In total we made about 5,000 pictures of the, of the house of Amines House and in the experience then you can walk through this house and meet him and speak to him. And in this process of making these pictures, sometimes the, the light was not so good, so we had to make you know, long exposure pictures and you can imagine like every photo taking seven seconds and you have to take 400 pictures in a room or is that, it takes a long time. So it was high, like high pressure and you can’t make mistakes. That was really difficult.

Justine: Wow. Yeah. 450, you know, perfection times for 50 that’s a complicated formula. Wow. This has been a very illuminating conversation. Thank you so much Gayatri speaking with us and I wish you more success and even more funding for your, for your two projects.

Gayatri: Thank you. Thank you so much Justine.

FREE COURSE VITAL KNOWLEDGE ABOUT VIRTUAL REALITY

UNCOVER THE BASIC PRINCIPLE

UNIQUE TO 360/VR

GET STARTED FOR FREE Home after war

Home After War was directed by Gayatri Parameswaran from NowHere Media in partnership with the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD). The experience takes the viewer into the tragic, real-life story of an Iraqi family’s return to Fallujah after being displaced from their home by war. Viewers walk through Ahmaied’s home, which still shows signs of damage, hearing his story and learning about the ever-present threat posed by IEDs and what it’s like to fear the home you once loved.

KUSUNDA

In the VR experience KUSUNDA, you explore the memoirs of Gyani Maiya Sen, an 83-year-old indigenous woman who is the last speaker of an endangered language. By using your voice to speak in Kusunda, you trigger interactive journeys into Gyani Maiyas past and learn about a unique language and culture.